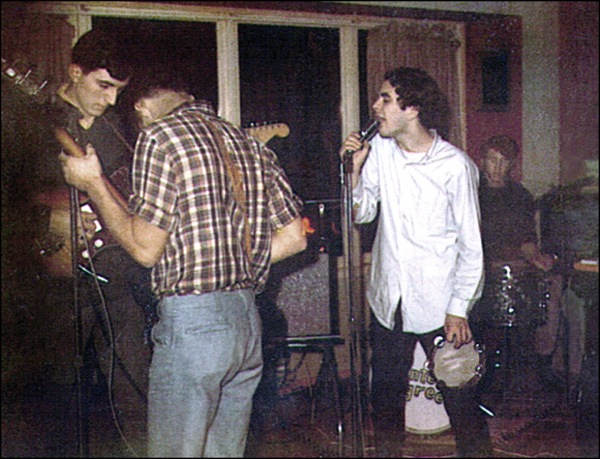

~ Brian Smith, Daryll Stelmaschuk, Me, Derek Solby in 1965

Since you and your mates have never had a reason to discuss songwriting, the subject suddenly becomes the elephant in the jam-room. Although the rhythm guitar player vaguely recalls someone calling out chord changes, and a beer being spilled on a notebook full of lyrics, he’s decided that songwriting credit should be split even-steven amongst the Beer Brothers (his choice for the new band’s name). Much of what you played on your Les Paul was extemporized … a lick here, a solo there … and your only clear memory of the evening was having to stop frequently because the drummer seemed to be having trouble catching the groove – so you’re feeling unwilling to share royalties with him. And although the lyrics for the songs seemed to come together surprisingly quickly, you’re considering changing some of the lame parts. This, you decide, will be your after-the-fact songwriting contribution, and justification for your share. The bass guitar parts were played by a friend who’d shown up late with a case of Red Stripe. This was his first jam. Some of the Beer Brothers privately resent his “Brother” status and question his right to any kind of royalties. The keyboard player is a big fan of the drummer and plays with him in another band. He’s the one who sang the lyrics and melody he’d learned from the drummer’s demos of the four songs. The drummer was the one calling out the chords and stopping the band when things got off track. He’s not happy with the sloppy playing on the recordings, and was considering taking his songs elsewhere – but now he’s stoked about the million dollar recording deal.

So what happens next? Politics, that’s what. At this juncture, with our imaginary record contract in the balance, anything could happen. At one extreme, the whole adventure could end in a Commitments-worthy stalemate, possibly concluding with a drunken Irish fist fight. More likely though, some kind of compromise will be hammered out. An acknowledgement of the drummer’s songwriting contribution would be a fair and just outcome, so let’s choose that hypothetical road for the Beer Brothers and consider what could happen next.

At the first official band meeting, the drummer’s demos are played and it’s unenthusiastically agreed that songwriting royalties for the four initial songs should go to him. In the following weeks though – after receiving advance money from the record company – the four other Brothers invest in recording setups not unlike the drummer’s. By the time you and your buddies meet up to jam some new tunes for the record, each player is packing a collection of freshly-written songs. There are 46 in all and only a dozen or so are required. To a layman, the solution might seem simple – just narrow it down to the best songs – but in this hypothetical scenario (and very often in real life) each player believes, not surprisingly, that his tunes are the best ones.

So what happens next? Politics again, of course.

With the musical direction of the band now at stake – further complicating the songwriting issue – tensions begin to mount. Your band’s overnight success has attracted press interest and your bass player, by virtue of his boyish charm and good looks, has been singled out. During interviews, he talks at length about his songs and the musical thrust of his band. The keyboard player, still tweaking mixes for his eleven tunes, now openly mocks the drummer’s “over-commercial” pop songs. The rhythm guitar player has increased his pot intake and tinkers constantly with a vintage Echoplex he’s borrowed to enhance his trippy dub songs. You’re confused. The drummer’s pissed …

Left to their own devices at this point, the BB’s could break-up, reshuffle personnel (“creative differences”) or work out another politically expedient compromise. As you can see from this admittedly accelerated and time-compressed scenario, these compromises come less easily as the potential for money and fame increases.

So who’s songs get on the album? Since I prefer happy endings, and because I’m making this up, I’ll predict that the record company introduces you all to a world-class producer who listens through the 46 songs and ultimately chooses to record only those written by the drummer. In fact, he likes those tunes no better than the others, but he’s learned that the record company president chose the four original drummer-composed songs – and the president signs his $50,000.00 cheque. To cover his ass professionally and creatively, though, he also insists that the band cover four songs that were hits in the sixties.

If I were in a malevolent mood, I could continue the story detailing how, after the release of the first hugely successful album, the producer sues the drummer/songwriter for a share of his royalties based on his contention that he contributed to the songs in the studio. Well-known songwriters might be called in for their expert testimony.

•

This isn’t particularly exaggerated. These kind of politics are more likely than not to arise. Some bands manage to co-exist longer before these issues begin to complicate things – and a few lucky crews, by virtue of some fortuitous alignment of the stars, sail through their entire careers with no significant political crises at all.

In a collaborative creative endeavour all things are possible and, as with creativity in general, breaking and bending rules and conventions keeps music interesting and alive. Any combination of input and talent can complete a successful creative project, but when money is injected into the equation, things can get complicated.

I’ll start working on part 5 now ...